Starting a farm-to-table restaurant is not that different from starting any other restaurant type. You’ll need permits and licenses and need to undergo health department inspections, among other things. Starting a farm-to-table restaurant requires a few different strategies than opening an eatery that relies on conventional suppliers. The greatest difference restaurant owners will notice is the time they spend researching farms and building vendor relationships. The major difference in starting a farm-to-table restaurant is sourcing your suppliers. Maintaining a constant supply of fresh, local ingredients sets farm-to-table restaurants apart from restaurants that rely on a few mainline suppliers.

1. Create a Farm-to-Table Restaurant Menu

The farm-to-table philosophy is, at its foundation, about authenticity. Beyond simply showcasing the provenance of a few ingredients, the majority of ingredients in a farm-to-table restaurant should come from a local source. Simply seeding a menu with a few local items is not the spirit of farm-to-table. This strategy is unlikely to resonate with customers who are willing to pay higher prices for local foods.

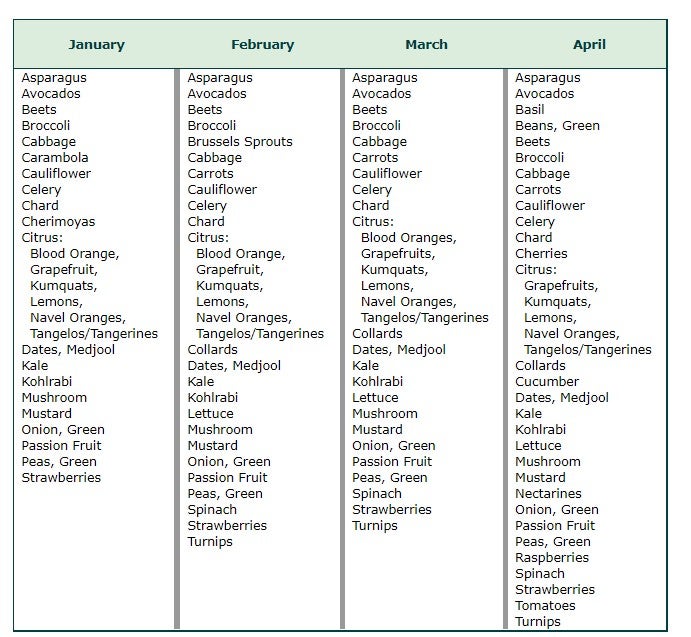

To capture that market, your farm-to-table menu should feature a majority of ingredients that can be traced to local sources. It is best to start with some research to determine what foods grow well in the restaurant’s location. Local agriculture groups are usually eager to help with this, and may have many online resources available. For example, California’s Southland Farmers’ Market Association publishes a seasonal guide to the fruits and vegetables of southern California on its website.

A simple internet search for your location and “fruits in season” or “vegetables in season” is a great place to begin. Reaching out to Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) businesses or talking to vendors at local farmers markets can also give restaurant owners a good idea of what local farms are already growing.

After writing a menu that features local ingredients, it is a good idea to consider the menu alongside your expected customer volume. Literally, imagine how much of each dish you expect to sell every week. Then calculate the quantity of each ingredient you will need to support that level of business. Doing this now will set you up for success in the next step.

Be Flexible.

This menu is just your jumping-off point, based on what should be available in your area. Be prepared to adjust your menu and make substitutions after you meet with farm vendors.

2. Find Farm-to-Table Restaurant Suppliers

Crops take time to grow. A plant that you want to eat in September was likely planted months before. For this reason, many farm-to-table restaurant owners begin sourcing suppliers a year before they plan to open their doors. Due to this timeline, researching and meeting farmers is likely the first task you’ll perform and one you’ll continue in the background while going through the rest of the steps below.

There are two main strategies for sourcing farm-to-table supplies: One is buying directly from local farms, the second is growing your own produce. Many restaurants do a little bit of both. Ultimately, you will include the costs and benefits of whichever strategy you choose in your business plan. Expand the sections below for more details about each approach.

2. Find a Restaurant Location

Unlike conventional concepts, farm-to-table restaurants need to consider accessibility to local farms when choosing a location. In suburban areas, this may mean being close to a major highway. In cities, this may mean access to a loading dock, a location in a commercial corridor that is not disturbed by early morning deliveries, or a spot near a popular farmers market. Danny Meyer’s flagship Union Square Cafe is an excellent example of all these qualities.

Demographics are another consideration when choosing a location. Millennial and Gen X diners tend to place more importance on the origins of the food they purchase than older generations. For this reason, a neighborhood with a high population of young professionals would be an ideal location for a farm-to-table concept. Having a profile of likely customers who live near your restaurant will also be useful in later steps of the opening process.

Building an operation around local foods can incur higher food costs than conventionally grown foods. A location that already has a commercial kitchen will save you money on construction costs.

Assess the Farm-to-Table Restaurant Competition

Part of finding your ideal location requires considering what other nearby businesses will complement or compete with your business. An active farmers market within a block of your location may support your restaurant with supplies, and also draw locavore diners into the neighborhood. If it offers a broad spectrum of prepared take-away meals, however, this market could also be a bit of a competitor.

In the restaurant industry, being near other food service establishments is not always a bad thing. Many towns have a “restaurant row,” a stretch of street or a section of a neighborhood known for having many eateries. When looking at locations with a high density of food service businesses, your main concern should be the level of customer traffic in the area. An area that is packed with several restaurants in a single block can be a great location for a new restaurant if that block is a high-traffic area.

When considering your competition, also consider your target customer. Ask yourself their age, income level, and what foods or issues they care about. Consider which nearby food establishments already support that customer. Note in detail how those establishments operate, their price point, the menu items they offer, what they appear to do well, and where they have opportunities to improve their operation.

Then, consider the niche that your business will fill in the market. What choices have you made to set your restaurant apart from the local competition? This information helps you gain insight into your operation, and much of it will be valuable for creating your business plan.

3. Figure Farm-to-Table Restaurant Projections

The restaurant metrics of a farm-to-table operation vary slightly from a conventional restaurant. Target food costs can fluctuate from month to month. For Example, when you buy a glut of fruit in the summer months to preserve and serve in leaner, winter months, your food costs will be higher in summer, but lower in winter. Restaurants that choose to grow their own produce will have associated labor costs to tend those plants as well as additional equipment or building costs to establish the crop.

Before opening, farm-to-table restaurant owners should set aside time to calculate their operational costs and make sales projections. Important figures include projected customer count, sales, food cost, labor cost, and break-even point. Expand the sections below for step-by-step pointers.

4. Write a Business Plan

Now is the moment to compile all the information you have gathered so far and put it in a format that will entice investors and banks to invest in your restaurant. A business plan is essentially a summary of your restaurant’s vision. A business plan is necessary to pitch investors and apply for business loans. Farm-to-table restaurants in particular should use their business plan to showcase their strategies for making the most of their farmer relationships and seasonal products.

Download our free restaurant business plan template to get started:

A restaurant business plan has several key features:

- Executive Summary: This is a one-page summary of your business. It should be a quick read that touches on each of the sections that follow. A sprinkling of mouthwatering language or evocative farm images can begin to set the tone for the rest of your proposal.

- Business Overview: This is a list of the basic information like your name, the name of the business, business address, phone number, email address, website, and social media handles if you have them. You should also list planned hours of operation here.

- Description of Your Concept: Here is the place to sell investors on your vision. Entice them with vivid descriptions of your food, beverages, and service style. If you have renderings of your finished space, or photos and bios of your farm partners, include them here.

- Sample Menu: The sample menu does not need to be your final menu; it is understandable that the menu will evolve before you open. This sample menu is an opportunity to make your potential investors’ mouths water and showcase your dynamic use of seasonal ingredients. Photos of finished dishes can be really impactful here.

- Location: If you have found your perfect location, include the street address and lease information in your business plan. In some highly competitive markets, however, you can move forward with your ideal neighborhood and a list of currently available spaces that meet your needs and budget.

- Operational Plan: Describe your management hierarchy. List bios of yourself and any principal collaborators or employees that you currently have such as a chef, general manager, and lead bartender. This is also the place to showcase the full list of farm vendors you plan to work with and discuss how you will feature their products.

- Market analysis: The market analysis should be an in-depth description of your target customer and target market. It should also include a description of your potential competitors and describe the advantages that may give your business the competitive edge.

- Financial Analysis: This portion of the business plan includes your projected sales, profits and losses, startup costs, and operational costs. This is where you show potential investors that you have done the math and prove that your restaurant can be profitable. This section should definitely include a break-even analysis that predicts the date when your business has recouped startup costs and begun to turn a profit.

Most restaurant owners rely on advice and assistance from collaborators like chefs, CPAs, or front of house managers to complete their business plan. Don’t be afraid to ask for help and input from others.

5. Find Funding

The restaurant world is full of stories of small restaurant owners who mortgaged their house and maxed out credit cards to get their restaurant off the ground. Though many begin with personal investment, restaurant owners frequently add outside funds from investors and small business loans. With your business plan in hand, it is now time to raise some money.

Ask Friends and Family

The first people that many small restaurant owners approach for funds are usually friends or family. While no one likes to think of the potential failure of their business before it is off the ground, it is wise to ask yourself if a particular relationship will survive if the friend or relative fails to see a return on the investment and if they can afford to live without this money for two years.

Some small business owners may find that preserving their relationship with someone is more valuable than that person’s potential monetary investment. If you want to give friends and family an opportunity to feel invested in your venture, a crowdfunding campaign for the purchase of a single piece of expensive equipment like a hydroponic system or irrigation for a rooftop garden can be a nice outlet for their good wishes.

Pitch Your Restaurant to Independent Investors

Restaurants are part of what makes a neighborhood or community vibrant and active. As a result, many restaurants find that other local business owners or entrepreneurs enjoy investing their money in restaurants. Restaurants can have several independent investors that invest varying amounts. Such investments generally come with perks like dining discounts and the ability to always get a table at a hot restaurant on a busy night.

When reaching out to independent investors, it is a good idea to retain the services of a lawyer who is familiar with the restaurant industry. These professionals can help you establish the terms of an investment and ensure that they are a good fit for your business.

Nervous about finding investors? Check out our full article on finding restaurant investors for tips and strategies.

Secure a Small Business Loan or Line of Credit

Even after raising some funds through family, friends, and investors, most small restaurant owners still seek out small business loans. Loans from private lenders or via the Small Business Administration can take weeks or sometimes months to process. A savvy small restaurant owner will apply for these funds at least three to six months before their projected opening date.

Generally, a small business loan will have a lower interest rate than a line of credit of the same amount. However, the interest clock on a line of credit doesn’t start running until you use it, and then only on the portion that you do use. So if you have a $100,000 line of credit, but you only use $20,000 of it, you are only charged interest on the $20,000 you used. In contrast, the interest on a $100,000 loan will compound regardless of how much of the loan you have used.

Learn more about applying for small business loans in our Guide to Restaurant Financing.

7. Design & Construct Your Restaurant Layout

A farm-to-table restaurant faces the same sort of challenges as any restaurant when designing a floor plan; this may include adhering to Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requirements, building codes, and health codes. Most restaurants budget 60% of their square footage for the dining room, or front of house (FOH) area, and 40% for the kitchen, or the back of the house (BOH).

For step-by-step guidance, see our full guide to designing a restaurant floorplan. Expand the sections below for niche, farm-to-table restaurant moves.

6. Obtain Permits & Licenses

Any new restaurant must be registered with the state in which it is operating. The procedures and fees will depend on the type of business you’re opening and will differ from state to state. Some states require businesses to pay a single flat fee annually, while others base their fee schedule on a percentage of sales. A general online search for “Business License” and the state you are operating in will direct you to the correct .gov webpage for your state.

It is good to start researching this early, as in some states it can take a couple of weeks to secure a business license. The costs can also vary greatly, ranging from $200 to $1,200. In addition to this state-issued business license, you will also need to obtain these basic business licenses:

- Employer Identification Number (EIN): This comes from the Internal Revenue Service and can be applied for online. There is no charge to obtain an EIN.

- Certificate of Occupancy: The process to obtain a certificate of occupancy from a local building department varies from location to location. Information for your area can be found by searching online for “Certificate of Occupancy” along with your city and state. These generally cost around $100.

- Resale Permit: This state-issued permit enables your business to purchase re-sellable items without paying sales tax on them. Costs are usually less than $50.

- Seller’s Permit: A seller’s permit identifies your business as a collector of state taxes; there is typically no charge for this state-issued permit. Most states, however, require a security deposit to ensure that sales taxes are covered when a business unexpectedly closes.

- Sign Permit: Local city governments generally have specifications about the size of any signs posted outside of restaurants. Costs range from $20 to $50.

Additional permits are related to health and sanitation. Beyond licenses from the local health department to enforce health codes, many towns require permits for dumpsters and grease traps. Grease traps are a plumbing fixture that intercepts the wastewater from food preparation to prevent grease and oil from creating problems in public sewer systems. These licenses are issued by various local health and sanitation interests:

- Food Service Licenses: The cost of these health department issued licenses depends on the size of your operation and usually ranges from $100 to $1000. Before final approval, the Health Department must inspect your restaurant in person to ensure you are operating within local health guidelines.

- Health Permit(s): One type of health permit covers your building and one covers the employees handling the food. Some states require that every staff member that handles food have an individual Food Handlers Certification. Costs range from $100 to $500; your local health department will list requirements in your area.

- Dumpster Permit: This permit is issued by local departments of sanitation; costs vary from city to city and depend on the size of the dumpster.

- Grease Trap Permit: Permits for grease traps run around $100 and are usually issued by local water or sewage boards. A plumbing inspector may need to approve the size of your grease trap before issuing a permit.

In addition to those basic permits and licenses, many restaurants will also need licenses to cover additional restaurant functions.

- Liquor License: State Liquor Control Boards or Alcoholic Beverage Commissions (ABC) issue these licenses. Costs can vary wildly, from $10,000 to $400,000, depending on whether you want to serve wine and beer or liquor.

- Cabaret License: In some cities, restaurants with live dancing and/or live music (even karaoke) will need a cabaret license. Issuing bodies vary by location (in Los Angeles they are issued by the police department), costs range up to $2,500, and they usually require filing a full set of the business owner’s fingerprints.

Some cities have additional license requirements. You may need an additional “off-site” liquor license if you plan to operate a bar at a catered event. As with several of the licenses mentioned above, information about additional license requirements can be found on your local state, city, or county government website.

See our guide to restaurant permits and licenses for step-by-step guidance on obtaining the permits your farm-to-table restaurant needs.

8. Purchase Fixtures, Furniture & Equipment (FF&E)

The higher cost of purchasing local foods combined with increased labor costs of processing whole ingredients can create tight margins for farm to table restaurants. Savvy owners will offset some of the higher costs by choosing lower cost furniture, fixtures, and equipment.

For example, mismatched table settings can give a homey feel to farm-to-table restaurants and cost a lot less than purchasing matching sets from a supplier. You may be able to save money by purchasing mixed boxes of plates and serving pieces from restaurant supply stores, antique shops, or Etsy sellers.

Furniture is exactly what you would expect: tables, chairs, and so on. Fixtures are installed items and built-in surfaces like lighting, bars, and banquettes. Equipment includes all the equipment necessary in the restaurant trade, including commercial ovens and dishwashers and a point of sale (POS) system. Expand the sections below for more details about the FF&E you need for a farm-to-table restaurant.

9. Hire Your Management Team

Ideally, the management team of a new farm-to-table restaurant will have some farm-to-table experience. However, because of the high level of menu flexibility, constantly shifting food information, and granular detail that orders may require, this is one case where true passion can be more valuable than experience.

In the front of the house (FOH), owners should look for managers who are skilled at training staff and have a plan for effectively communicating information on the fly. In the back of the house (BOH), kitchen managers should be well-versed in common ingredient substitutions and eager to change dishes regularly.

Industry specific job posting sites are great places to find individuals with experience. Using an industry-specific site saves you a ton of time sifting through irrelevant resumes of applicants with no applicable experience. Check out sites like Culinary Agents, Good Food Jobs, and Poached.

Speed up your management search by using our guide to writing a restaurant manager job description, which includes a free, downloadable template.

10. Hire & Train Line-Level Staff

You can find hourly staff with a passion for the farm-to-table philosophy on several of the same websites that you used to find managers. If you are a casual restaurant or are able to train novice serving staff on the finer points of carrying plates and setting tables, sourcing front of house employees with a farm background is a good idea. Those staff members will come prepared with food knowledge that you would otherwise have to teach.

In the kitchen, you ideally want candidates that have experience working with local foods. These foods typically arrive in a higher state of ripeness and will have a shorter shelf life than conventionally sourced foods. If you are training novice cooks, it’s a good idea for you and your chefs to encourage innovative ideas for using every part of the fruits, vegetables, and meats that arrive from local farms.

Carrot tops can become pesto. Roasted bones and trimmings from onions, celery, and tomatoes can be used to make rich broths for soup. You want to train your kitchen team to squeeze every ounce of usefulness from these higher priced local foods. This mindset may be second nature for some cooks, but it is a great ethos to instill throughout a tight-margin businesslike a restaurant.

Read our guide to hiring restaurant staff to help speed up your processes.

11. Advertise & Build Community

With your staff trained and your supplies stocked, your grand opening is close at hand. Decide on a date and time for opening your restaurant and reach out to your local community. Let them know who you are and what you offer. Research local restaurant reviewers or writers for your local papers. Look up food bloggers who are based in your area. Patronize nearby businesses and let them know about your planned opening.

Advertising on social media is a great, cost-effective way to reach nearby customers. Spend a little money on a Facebook or Instagram promotion. Ask your staff, neighboring businesses, and farm partners to spread the word to their networks. Farming communities tend to be as close-knit as restaurant communities so the opportunity to taste a neighbor’s products—or their own—is a big selling point.

Get step-by-step guidance in our guide to restaurant marketing.

12. Host A Soft Opening

Before you open to the public, take the time to host a soft opening. This is a time when you invite family and friends to try the menu, look at the space, and interact with your team. This is also the time to show your farm suppliers how you have showcased their wonderful products. There are few things in restaurant life more moving than seeing the look on a farmer’s or forager’s face when they see their heirloom carrots or wild morels displayed prominently on a plate.

Most soft openings are at least partially “hosted” with the restaurant covering the cost of all the food and non-alcoholic beverages. A soft opening should be fun and exciting for your guests, but it is not just a big party. For both staff and owner, a soft opening is the best opportunity to make sure that everything you carefully planned will work properly before you open.

Learn about what a soft opening is and how to plan a successful one in our guide to soft openings.

Converting a Restaurant to Farm-to-Table

Shifting a conventional restaurant to a farm-to-table operation is a slightly different process than opening a new operation from scratch. You won’t need to write a business plan or find a new location, a converting restaurant should create a new menu then research local food vendors, and develop new standard operating procedures (SOPs) for ordering products. It may also be necessary to set aside time for training staff on new food items and cooking skills.

- Update your menu: The first order of business is to update the restaurant menu to reflect what local foods are available in the current season. This may mean reducing the overall size of your menu. It is important to remember that your goal is to focus your restaurant’s menu; a smaller menu does not mean it is a lesser menu.

- Find vendors: Contact local farms, foragers, and farmers market vendors. Let them know the inventory volume you need, and ask if they can provide the amount of product you will need on a weekly basis. A fully operational restaurant with sales data to back up their sales projections is definitely a less risky prospect for a local food supplier. So you are well positioned to ask if farms will grow a particular item specifically for your restaurant.

- Update SOPs: You will need to re-write SOPs for placing orders as well as update recipes to include a list of seasonal substitutions. A menu that changes more frequently will also require a high level of communication across your staff from the kitchen to the FOH. If you do not currently operate with daily pre-shift meetings to share menu updates and new dishes, you may need to start.

- Train your team: All of these updates translate into the next step—training your staff. Schedule time for both the FOH and BOH teams to learn the new menu and new SOPs. Most restaurants do this by closing to the public for a lunch service. During this time, the kitchen staff prepares all of the new menu items and the whole restaurant team sits down together to taste them and take notes.

- Host a soft re-opening: This should be just like the soft opening you probably held before you opened your initial restaurant. Just like when you first opened your doors, a soft reopening will allow you and your staff to test every system you just updated.

Farm-to-Table Restaurant Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Farm-to-table restaurants are straightforward concepts. These are the most common questions I hear about farm-to-table restaurants:

Last Bite

Starting a farm-to-table restaurant is hard work, but it can be incredibly rewarding. Not only does the restaurant style support local food producers in your community, it caters to a dining public that is increasingly interested in buying local foods. In addition to the usual tasks of finding a great restaurant location and writing a business plan, farm-to-table restaurateurs should expect to spend several months finding local farmers and foragers and building relationships with them.

ALSO READ